20 Of The Best Blues Guitarists of All Time

Whether the blues took its form because of the instinctive three-chord, 12-bar pattern, or whether popular music adopted the form from the blues can never be known for certain, since its field holler and juke joint origins predated recording. What is known is that what we know today as the blues grew from the Mississippi Delta and followed the great river north, becoming urbanized along the way.

When talk turns to great blues guitarists, there has to be a tip of the pork pie hat to Leo Fender, who created the mass produced electric guitar, the instrument that captured the imagination of so many on the list. Innovator Les Paul lent his name to the model synonymous with so much of the British blues idiom, along with Fender’s Telecaster and Stratocaster.

Some of the greats are associated with one guitar model, sometimes even just a single instrument, while others -- perhaps Eric Clapton, most notably -- move between guitars while exploring their muse. As with any list of this nature, there are omissions and points for disagreement, but any discussion can rightly include these players.

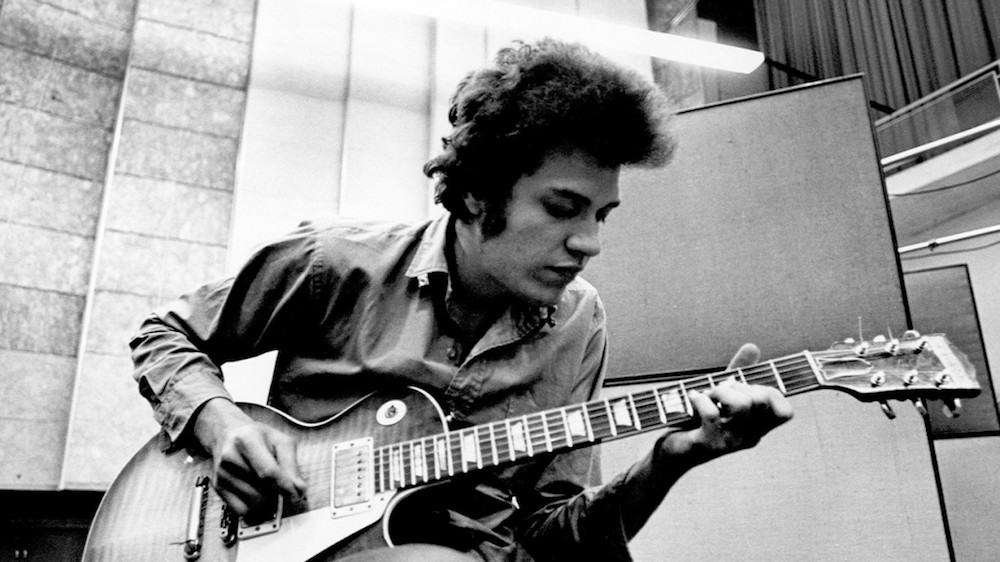

Rory Gallagher

Cork, Ireland isn’t as far away from the Delta as you can get, but it’s certainly far enough. Rory Gallagher emerged in the 1970s as hot blues Strat slinger. Paying dues in the 1960s with Irish show bands and his own group, Taste, Gallagher was at his peak in the 70s, recording eight studio and two live albums.

Despite the heavy output, Gallagher generated only cult popularity. His prowess was well regarded by other players and fans of contemporary blues, but mainstream success proved elusive. His style owed plenty to his ability on alto sax, phrasing on guitar much as a reed player might.

Yet there was always an Irish lilt to his style and a heavy dependence on “slash” chords -- the guitar method of sounding chord inversions, such as playing a D chord over an F# bass note. Check out Taste’s “Blister on the Moon” for one of the earliest examples in Gallagher’s oeuvre. Various live versions of “Tattoo’d Lady” demonstrate much of his development over time. Gallagher died in 1995 of liver failure.

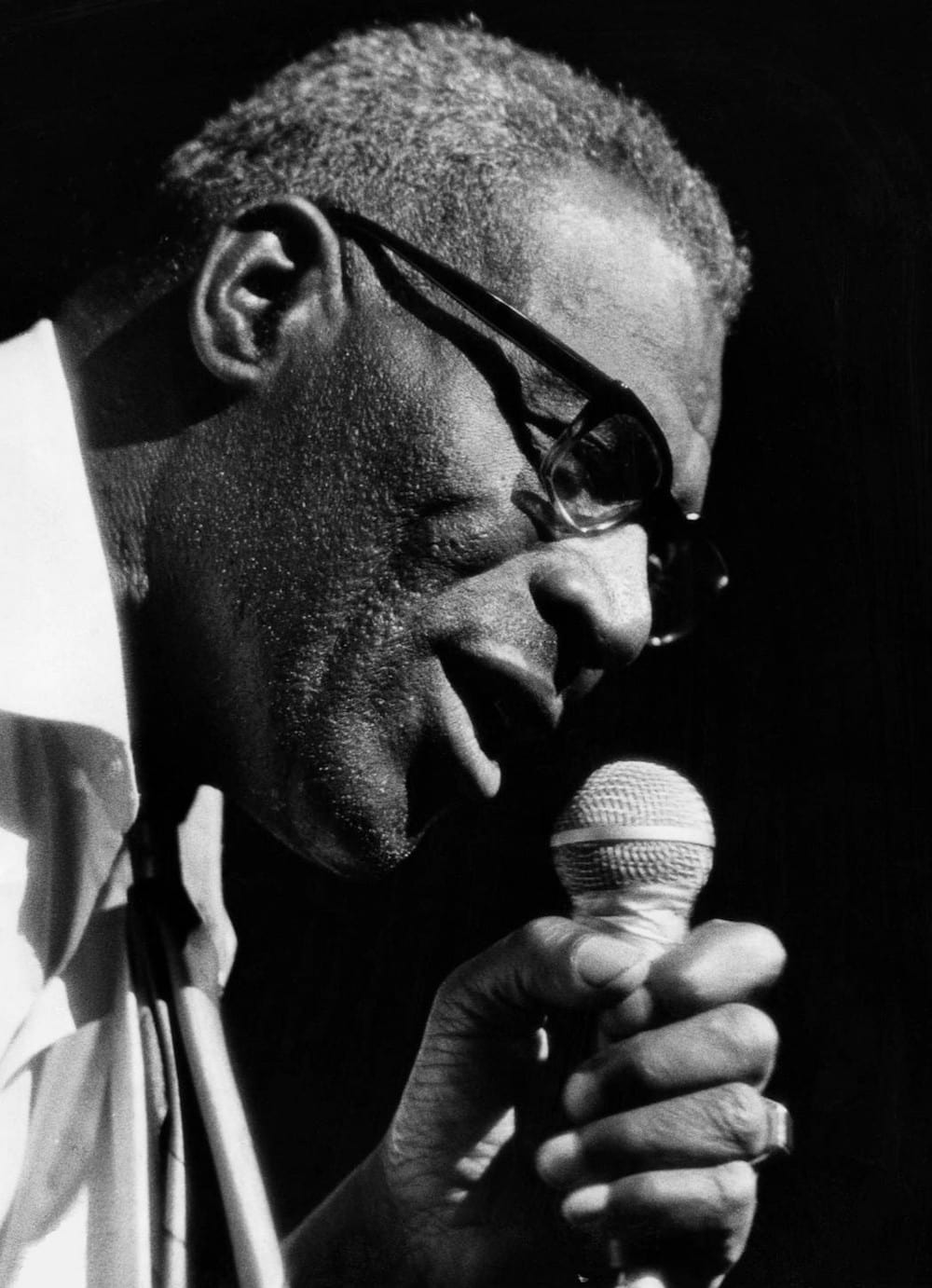

Howlin Wolf

Like his stage name, Chester Arthur Burnett was a wildman when it came to music, as well as a songwriter of tremendous influence. “Howlin’” is endemic to his style. A raspy voice projected over his instrument, Wolf began his musical adventure with the diddley bow, a one-stringed, primitive instrument that led many early bluesmen to the guitar.

“Smokestack Lightning” was not only covered by many British acts, such as the Who, Manfred Mann, the Animals and the Yardbirds, but the 1956 original hit the charts ten years later in England.

Adept at blues harp as well, Wolf’s reputation as a live performer remains large in his legend. His hypnotic grooves provided a solid base for the howling vocals and improvised solos. A long-time association with Hubert Sumlin added a two-guitar attack that, while not virtuosic, was guttural and forceful in the best Delta fashion. Wolf passed away at the age of 65 in 1976.

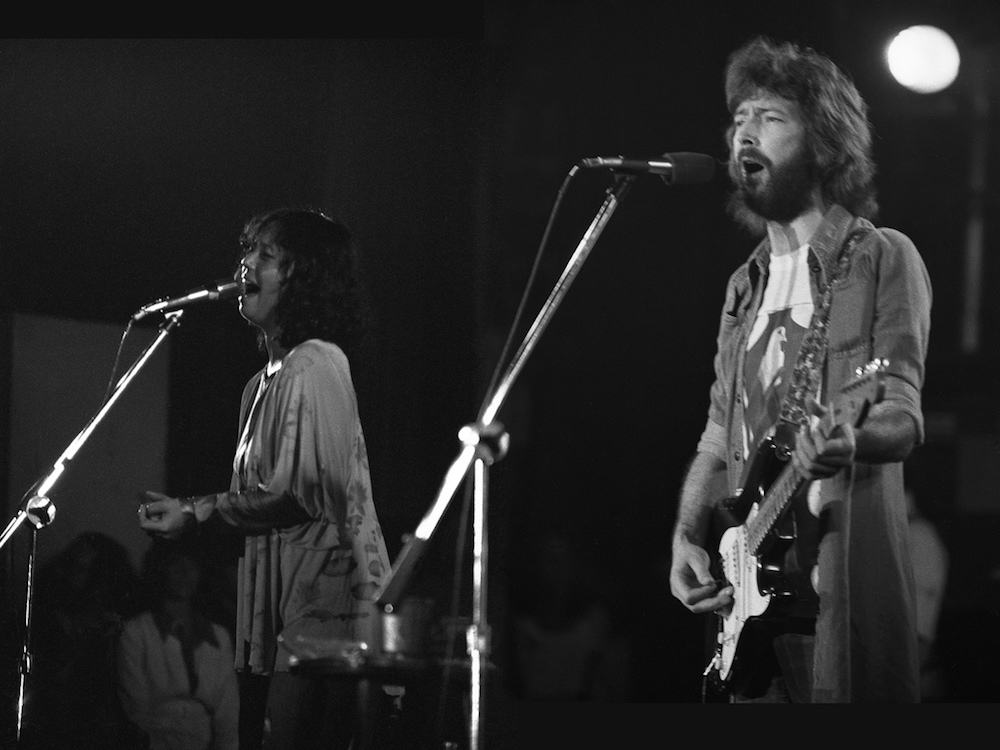

Eric Clapton

The “Clapton is God” graffiti around London in the 1960s is legendary, particularly when only two years before, the future guitar messiah was trembling over single spot solo opportunities in the early blues jams and halls around the U.K.’s capital.

Perhaps no single guitarist holds as much responsibility for bringing blues music into mainstream popularity. A disciple of Robert Johnson, Eric Clapton absorbed blues from all the major black American players, distilling their sounds through a Les Paul and Marshall stack in the 1960s to create a compressed, warm timbre he called “woman tone.”

While frequently struggling as a blues purist, his greatest moments came as an interpreter. While Cream and Blind Faith -- two of the original rock supergroups -- drifted substantially from pure blues, these can be seen in hindsight as essential to future projects, such as Derek and the Dominoes and his solo albums of the 1970s.

While these ventured away from Clapton the guitarist and established Clapton the songwriter, later albums such as “From the Cradle” and “Me and Mr. Johnson” moved back toward Clapton’s interpretation of essential blues as a complete performer. “Layla,” from the Derek and the Dominoes period, represents all the elements that Clapton brought to his career.

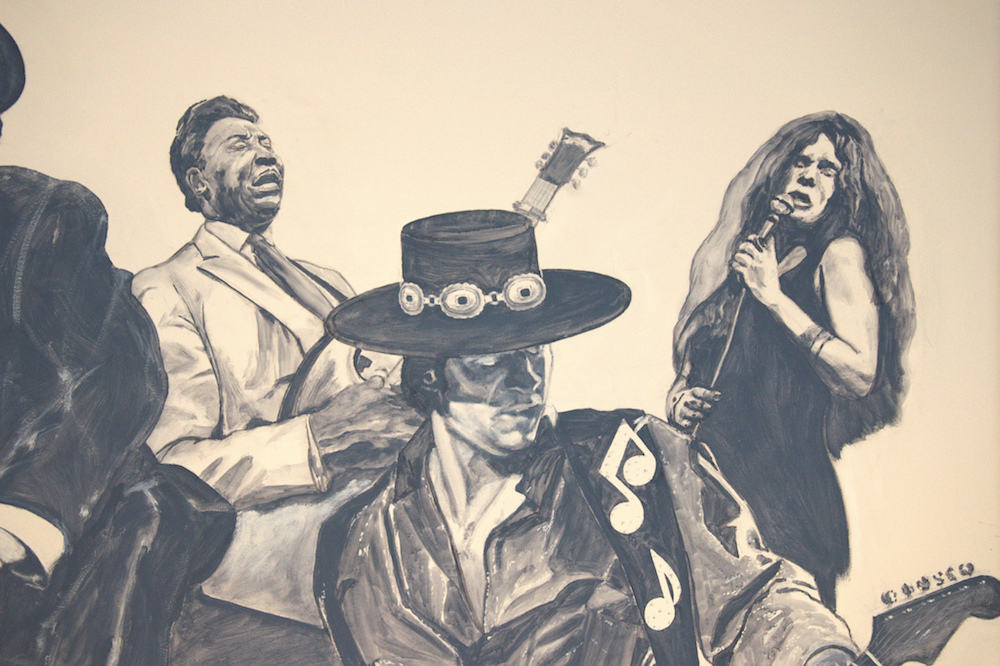

Jimi Hendrix

While Jimi Hendrix incorporated the blues into all his playing, he transcends the label of blues guitarist unless you add “from outer space.” His best work is otherworldly, touching on blues but defining rock guitar tone in ways that still sound fresh today.

Hendrix started his music career in 1963, after discharge from the army. In four years, he was the toast of London, playing a cover of “Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band” on the stage of the Saville Theater, three days after the release of the Beatles’ seminal album.

Closing out the original Woodstock Festival two years after that, Hendrix’s version of “The Star Spangled Banner” encapsulated the turmoil of Vietnam America. Though his recording career was brief, it was prolific and innovative. Able to play convincingly in any style, the effect Hendrix had on Eric Clapton led the latter to claim his life completely changed after hearing Hendrix play.

Clapton covered “Little Wing” for a Hendrix tribute years after the death of perhaps rock’s finest instrumentalist, but the Hendrix original sums up everything -- blues and beyond -- that the man brought to music over his short life.

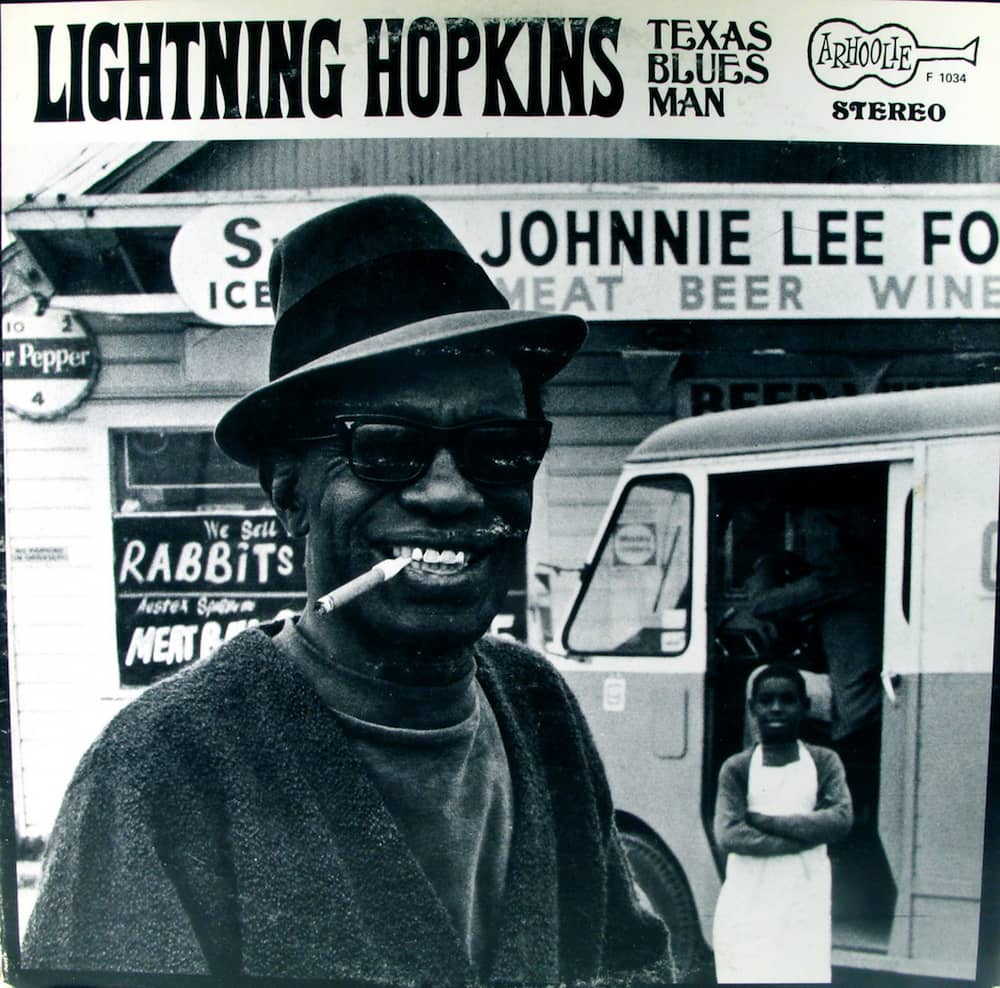

Lightnin' Hopkins

Check out Lightnin’ Hopkins’ solo acoustic version of “Baby Please Don’t Go” for a tutorial in the capability of the instrument as a country blues beast. Providing bass, chord structure and soloing with just two fingers on his right hand, Hopkins developed his style in the tradition of Delta masters like Robert Johnson, but giving polish and rhythmic purity that transcended the players who came before him.

In fact, that steady, driving rhythm influenced later British combos like the Rolling Stones, who could build a five-piece blues band around Hopkins’ sound. Yet, as solid as his style could be, it is overlaid with a loose and free form vocal phrasing. Listening to Hopkins and then to British vocalists such as Mick Jagger and Eric Burdon, and the influence of Hopkins as a singer is also evident.

Hopkins became active in the late 1950s as a folk blues artist, exposing his music and style to wider white audiences. As his playing includes fills that later became part of the lexicon of white electric blues, his influence cannot be understated.

Perhaps the most prolific bluesman in terms of album releases, Hopkins died of throat cancer in 1982.

Stevie Ray Vaughn

Associated closely with Stratocaster-style guitars, Stevie Ray Vaughn emerged as a hero of electric blues following his mainstream introduction as a session player on David Bowie’s “Let’s Dance” album. Long-time Bowie guitarist Carlos Alomar wasn’t involved in the “Let’s Dance” session, and Bowie gave the young Texas bluesman a wide leash to spice the album.

The timing couldn’t be better, as SRV’s own “Texas Flood” album released in the same period, featuring the definitive SRV track, “Pride and Joy,” a top 20 hit when the charts were loaded with the heaviest of 1980s synth-based music.

SRV’s style was borne of the Strat and technology in the form of cranked Fender amps fed by a Tube Screamer style guitar pedal. This combination, combined with guitar necks refitted with jumbo frets and his inimitable touch, defined electric blues for the modern era. Tragically, SRV died in a post-concert helicopter accident at the age of 35.

T-Bone Walker

Musicians as accomplished and influential as B.B. King and Chuck Berry cite T-Bone Walker as a key influence in their own careers, and it’s perhaps as a musician’s musician that Walker is best remembered, after his seminal song, “Stormy Monday,” a perennial standard for almost any blues-based cover band.

Walker became an accomplished stringed instrument player, learning mandolin, ukulele, violin and banjo from his father. Starting his professional career behind Blind Lemon Jefferson when he was only 15, Walker later put together his own band and featured with other dance orchestras.

His recording career started in 1939, but was most productive between 1946 and 1960. Through failing health, his career took a back seat through the 60s and Walker passed away in 1975 from pneumonia after a series of strokes.

Peter Green

If there’s a band with the proverbial feline nine lives, it’s undoubtedly Fleetwood Mac. Those familiar only with its success from the 70s onward may be surprised by its mention in an article on blues guitarists, yet the band was formed in 1967 by guitarist Peter Green as a blues vehicle, part of the British second wave of blues bands of the later 1960s.

Green was certainly around for the first wave, replacing Eric Clapton in John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers. It was there that he met Mick Fleetwood and John McVie, and the name “Fleetwood Mac” was coined by Green as the “group” behind an instrumental song that Green recorded with the duo as rhythm section. Curiously, Green formed Fleetwood Mac without commitment from McVie, who joined later.

B.B. King said of Green’s playing: “He has the sweetest tone I ever heard,” and Green’s regard with other guitarists is equally high. Check out “Albatross” from Fleetwood Mac as evidence of his innovative and soulful playing. Green left the band in 1970, but drug use and mental illness kept him out of the limelight.

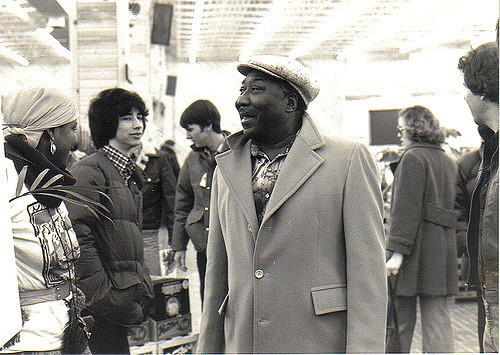

Muddy Waters

If ever there was a mold made for the quintessential black bluesman, it would probably resemble McKinley Morganfield, better known as Muddy Waters. Though a distinct and influential guitarist, the instrument didn’t define Waters as an artist. In one of his highest profile appearances during The Band’s “The Last Waltz” movie, it was as singer only, with his resonant baritone voice defining the sound of blues with the impassioned performance of the aging blues hero.

It was Waters’ recording “Rollin’ Stone” that gave the young English band its name. Known for his style and flashy dressing as well as his musical prowess, Waters brought the sound of urban blues to Chicago with his bands of the 50s, following the start of his recording career in 1946 and eventually ending up on the Chess Records label.

Often highlighting the songwriting of Willie Dixon, Waters’s brand of amplified, citified blues serves as the direct link between the Delta and blues-based rock. Waters died peacefully at the age of 70.

Skip James

Skip James may be the most obscure artist on this list, but those on record citing his influence is as long as any more visible artists. Using an open-tuned minor key combined with fingerpicking, James provided a different take on blues, often crossing into other genres, such as gospel and folk styles.

Perhaps the definitive James recording is his “I’m So Glad,” from 1931, later recorded by Eric Clapton and Cream. James adapted the tune from a song called “So Tired.” His fingerpicking defies labelling as blues, evoking country and bluegrass phrasing. Another one-man band on an acoustic guitar, James’ playing and phrasing found its way into the styles of many artists through subsequent blues eras.

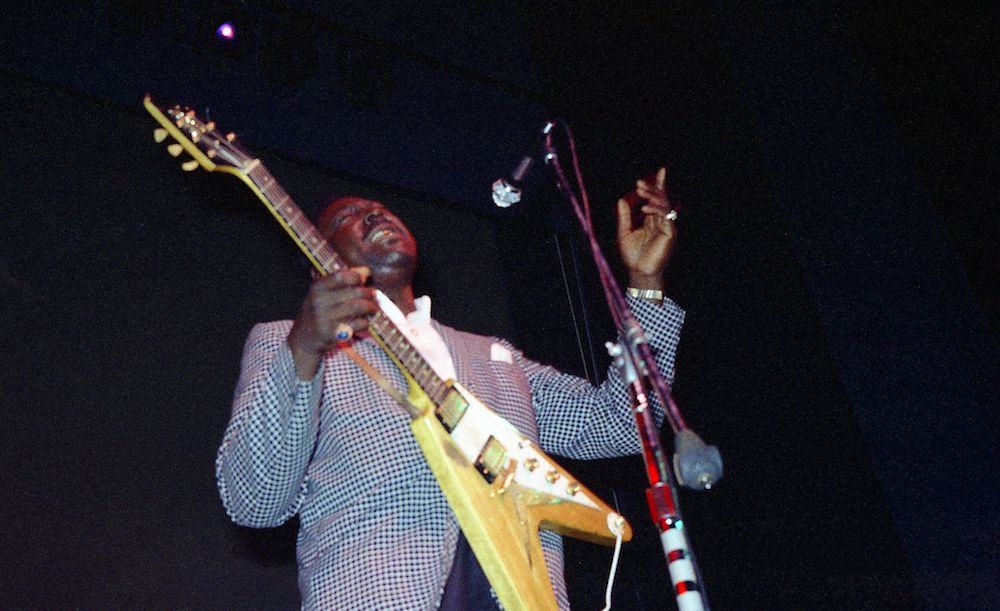

Albert King

Along with B.B. and Freddie, Albert is the third of the Three Kings of blues. A left-hander known for playing a Gibson Flying V guitar, his right-handed version flipped over and, except for the position of its controls, didn’t appear to be an upside-down guitar, though in fact it was. In later years, he did play dedicated left-hand versions of the guitar.

Known as the Velvet Bulldozer, recognizing his smooth voice and linebacker size, King’s ultimate moment came in 1967 with the release of “Born Under a Bad Sign,” from the album of the same name. Other high points of his career came with his 1977 guitar duelling at the Montreux Jazz Festival opposite Rory Gallagher and a late career pairing with Stevie Ray Vaughn for a Canadian television program.

King died of a heart attack in 1992, two days after his last gig.

Joe Walsh

A member of Ohio’s James Gang for three years between 1968 and 1971, Joe Walsh may be an unusual name on a list of great blues guitarists. Certainly, he’s a great player, but known as much for his time with the Eagles and solo success, his credentials as a core blues player aren’t strong.

Yet, his soloing is well versed in the five-note pentatonic scales upon which much of the blues guitar idiom is based. While the song itself has nothing to do with blues form, Walsh’s 1978 Number 12 hit, “Life’s Been Good,” parodies the trappings of rock stardom while featuring massive guitar sounds that carry much of the song.

As a primer for Walsh-ian phrasing and and post-modern pentatonic solos, “Life’s Been Good” stands on its own as a descendent of the original Chicago electric blues styles.

Mike Bloomfield

Another blues player taken too soon, Mike Bloomfield was much like Rory Gallagher in that his background was world’s away from the Delta origins of blues music. Privileged, Jewish and white, Bloomfield did have the advantage of growing up in Chicago in the 1950s.

While Bloomfield’s formative years were spent on the southside of Chicago, it was with white bluesmen Paul Butterfield and Elvin Bishop that he gained renown as a member of the Paul Butterfield Blues Band.

Playing on Bob Dylan’s 1965 album, “Highway 61 Revisited,” Bloomfield also accompanied Dylan at the Newport Folk Festival, infamous as Dylan’s first electric show. Bloomfield’s playing on the live version of “Maggie’s Farm” defines him as a soloist of first order, putting Dylan’s tune into a new and legitimate place, with stinging Telecaster tones for which he was noted.

Dead of a drug overdose at age 37, the circumstances surrounding Bloomfield’s death remain shrouded in mystery, curiously befitting the wild and short ride of the Jewish guitar hero.

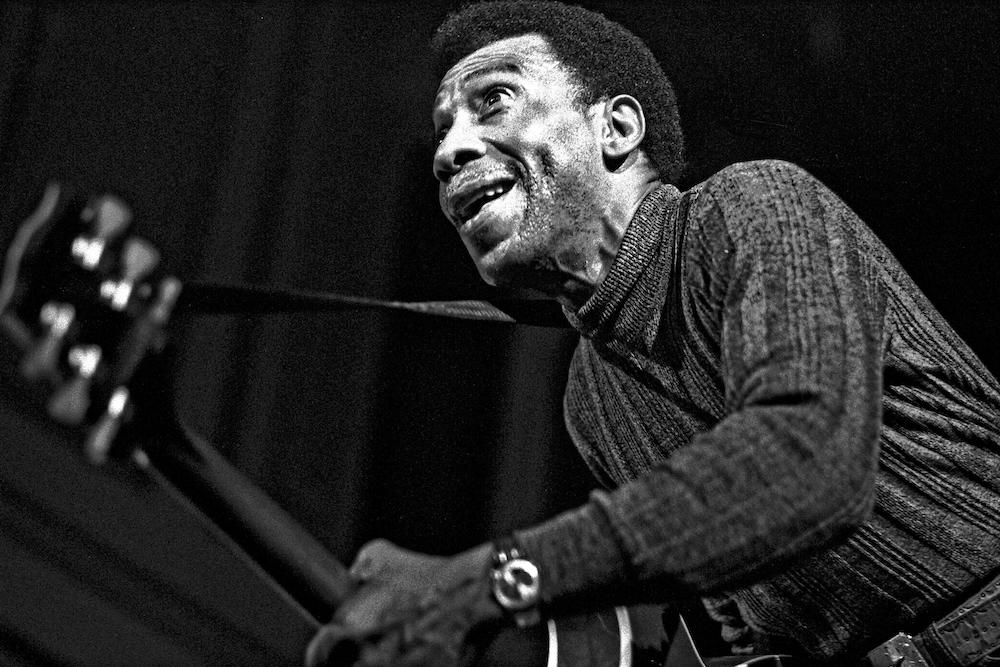

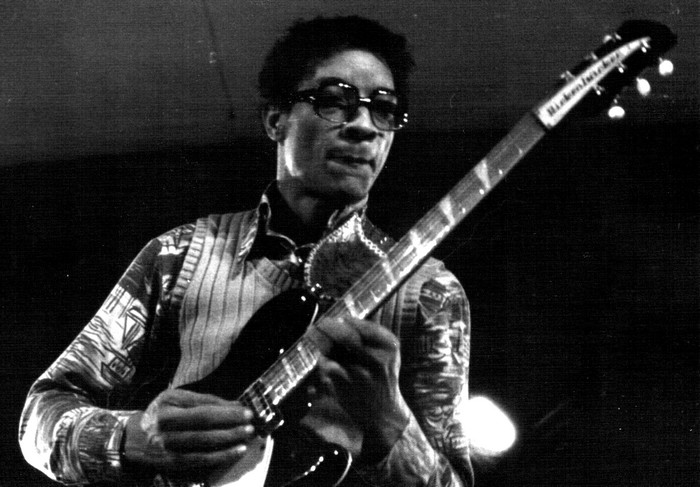

Hubert Sumlin

Playing guitar until the day he died at 80 years old, Hubert Sumlin navigated the blues landscape as part of the Chicago electric blues scene. Most closely associated as Howlin’ Wolf’s guitarist, Sumlin also did a stint behind Muddy Waters.

Sumlin broke out as a solo artist only after Wolf’s death, but he remained prolific and active. Perhaps more than most of the converted Delta players who crossed into electric blues, Sumlin preserved the essence of the Delta in his playing, though he was certainly capable of inspired single-note leads. Much of his tone owes to the use of bare fingers rather than using a pick. Check out Howlin’ Wolf’s “Killing Floor” for a distinctive impression of Sumlin’s lead guitar.

Elmore James

Himself a disciple of Robert Johnson, Elmore James was an early loud, electric bluesman whose influence resonated with artists of the early British blues community. Billed as the King of the Slide guitar, James frequently used hollow bodied guitars fitted with pickups. His stinging double stops predate their cleaner use by Chuck Berry.

James was down and dirty, pushing amps beyond the edge, pioneering distorted electric tones that generated as much excitement as his over the top high tenor voice. Perhaps no song encapsulates James’ influence as much as his cover of Robert Johnson’s “Dust My Broom.”

John Lee Hooker

With feet planted in both the Delta tradition and Chicago blues, John Lee Hooker proves difficult to categorize even today. With solid grooves and fluid structure, his playing and singing remain distinct, no matter the backing, be it solo acoustic or full band electric.

His greatest song, “Boogie Chillen,” came just a year after his first recording in 1948. The song is viewed by many as a precursor to rock and featured as one of the RIAA’s Songs of the Century. Just Hooker’s voice and electric guitar, “Boogie Chillen” features all the hallmarks of his style, from the hypnotic groove and tempo changes to serve the song.

In 1989, Hooker recorded “The Healer,” featuring duets with a number of contemporary artists, bringing him back into mainstream popularity at the young age of about 76 (his actual birth date isn’t known). Hooker remained an active performer and recording artist until his death 12 years later.

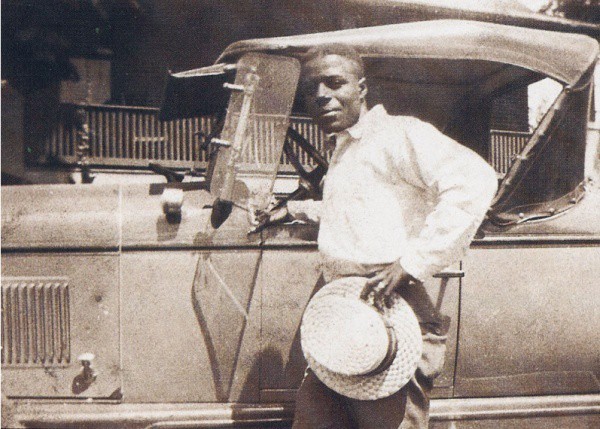

Son House

As with many early bluesmen, Son House came through rough circumstances in his early life. Married young, House spent a few years in prison after killing a man in self-defense. At one time a preacher, House changed his pursuits in life after hearing the sound of bottleneck guitar.

Though he had recorded earlier, it was Alan Lomax’s 1941 Library of Congress recordings that provided the body of work for which House later gained recognition. It wasn’t until the mid-1960s that House was rediscovered as a living blues originator, having spent the years after recording with Lomax as a railroad porter and chef.

“Father of the Delta Blues: The Complete 1965 Sessions” may overstate House’s role somewhat in the grand scheme of the blues, but the album certainly hit at an opportune time for both House’s fortunes and the world of recorded blues music.

“John the Revelator” from that album exemplifies House’s approach to folk blues music that, were it not for Lomax and later producer John Hammond, may have been lost to future generations.

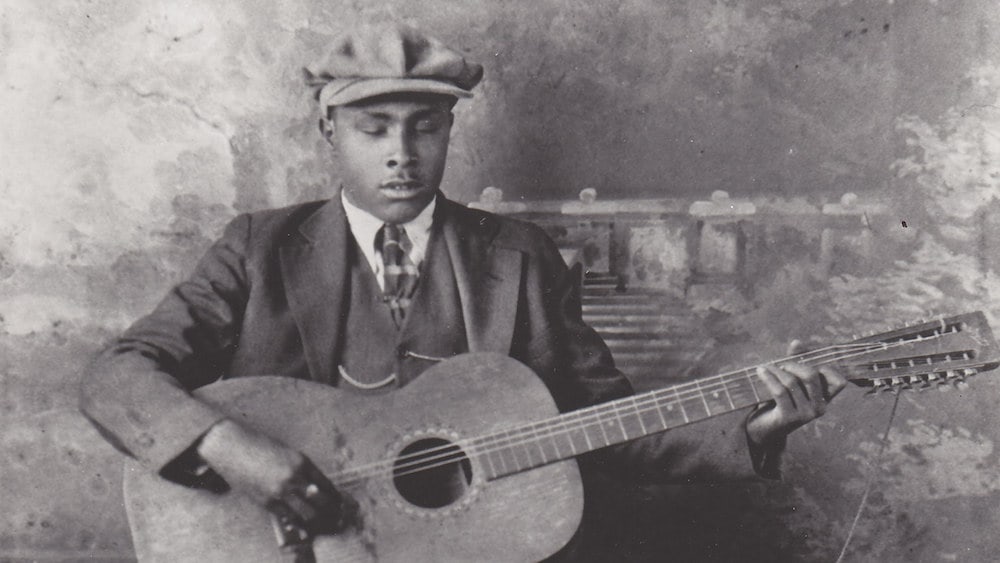

Blind Willie McTell

Piedmont blues stemmed from the southeast, and shares much with bluegrass, not unlike the fingerpicking style of Skip James. Blind Willie McTell stretched the blues over to the style of ragtime, itself an early jazz form. His fingerpicking style, using the relatively rare 12-string guitar, alternated with slide guitar to provide a unique take on early folk blues.

“Statesboro Blues” demonstrates the qualities of McTell’s style. For a recording originating in 1928, the song is remarkably timeless and mellow for early blues. McTell’s voice is clear, controlled and well modulated, while his guitar accompaniment flirts with elements of blues, ragtime and bluegrass, with just enough slide features to plant it firmly in the blues genre.

The song also became one of the tunes associated by the next entry in our list.

Duane Allman

Providing one of the most distinctive electric slide tones of the 1960s and 70s, Duane Allman provided the impetus to the Allman Brothers’ version of “Statesboro Blues” from the “At Fillmore East” album. While guitarist Dickey Betts delivers a fine solo in conventional style, Allman’s slide guitar steals the stage.

If it were his only recorded solo, that track alone would seal Allman’s reputation as a great blues guitarist. However, his playing on Derek and the Dominoes’ “Layla and Assorted Love Songs” took Allman’s work to a realm beyond the blues.

His sinewy slide duets with Eric Clapton cement the place of that album in rock history, and Duane Allman’s place as a guitar hero who also met an early demise at age 24 in a motorcycle accident shortly after the release of the “At Fillmore East” album.

Memphis Minnie

The blues in general, and blues guitar in particular, remains largely a man’s game. Yet Lizzie Douglas, better known as Memphis Minnie, not only made it in this man’s game, she left a trail of influence that connects directly with Led Zeppelin. Recorded with her husband, Kansas Joe McCoy, she wrote “When the Levee Breaks,” one of Zeppelin’s distinctive songs from its famed IV album of 1971.

In finest blues tradition, Minnie duelled with guitarist Big Bill Broonzy in a “cutting contest.” Each sang two songs, competing for a bottle of whiskey and a bottle of gin. By Broonzy’s account, Minnie won handily.

“Me and My Chauffeur” with third husband, Little Son Joe, shows Minnie off in fine form, singing and soloing over Joe’s accompaniment. A classy and independent lady with more than her share of toughness in a tough business. Laying a path for other blueswomen to follow, Broonzy felt that Minnie was the equal of any male as a player and performer.

In Conclusion

Twenty places is not nearly enough to cover those who brought taste, innovation and virtuosity to the musically limited confines of the blues music form.

As a launching point for expression that’s both visceral and prolific, the great blues guitarists live on, their comparative greatness debatable until their recordings disappear.

Great thanks to r/Blues on reddit for helping us narrow down the long list of many great Blues guitarists!

Leave a Comment

5 comments

Joe Walsh? Really? =-l

Yes, sir.

What about Keb Mo , Tracy Chapman , Bonnie Raitt , Blind Lemon Jefferson… I can go on and on , so list is way longer than 20 even going back to the 19th Century… But I dig the list.

rory Gallagher..finally someone who has posted a true and deserving article..

Freddie King?